Dementia Waikato is a Charitable Trust providing support and information for people affected by dementia throughout the Greater Waikato region. Our experienced staff are caring and knowledgeable.

At Dementia Waikato we provide information, education, support, advice, and personal advocacy for people with dementia, their families and whānau, and those who are close to them. A diagnosis of dementia brings up many issues and we help people negotiate their way forward in a way that suits their circumstances.

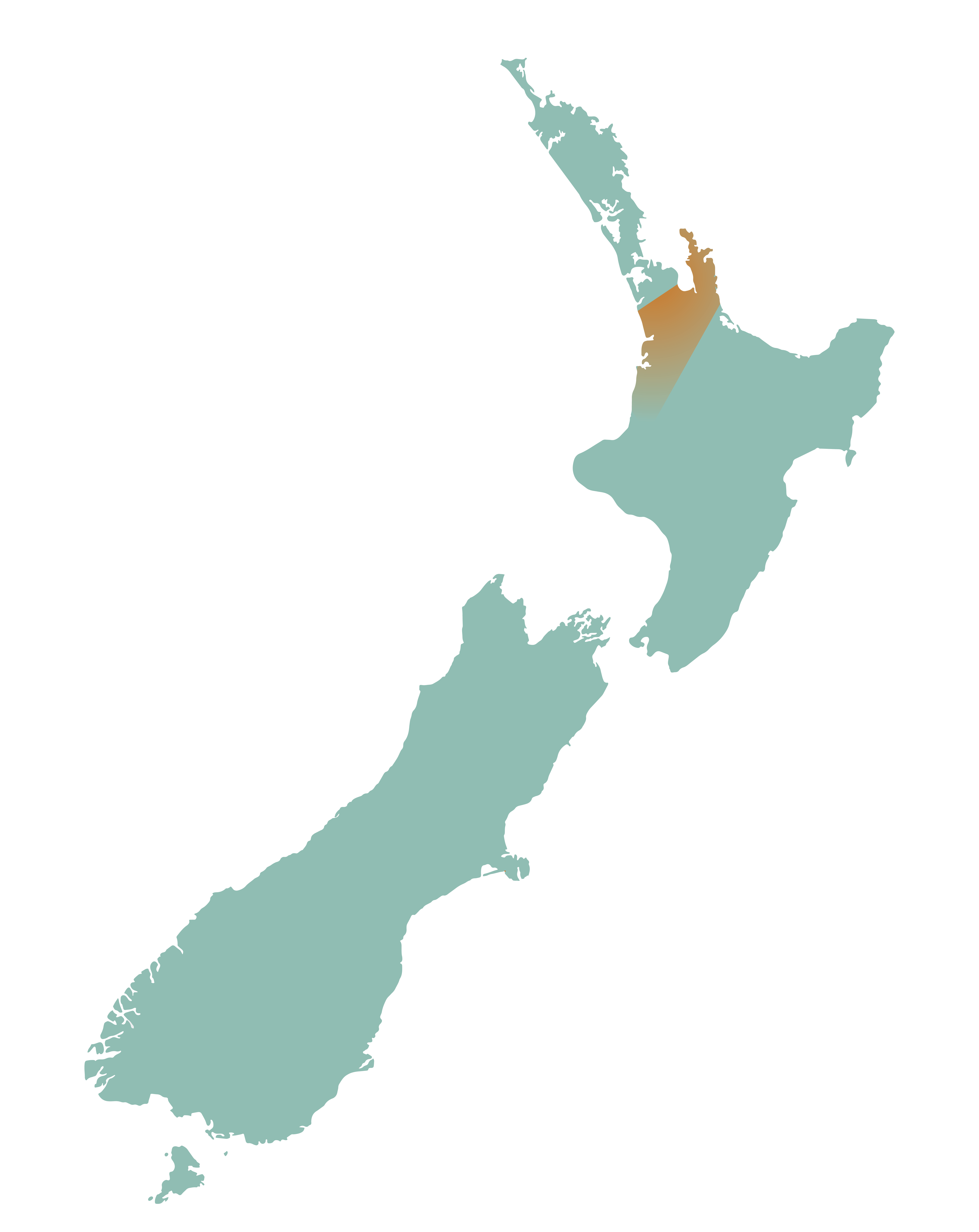

Dementia Waikato Support Area